Despite decades of research into gastric cancer, commonly known as stomach cancer, it still claims many lives around the world and its causes are proving more complex than we once thought. Fortunately, new discoveries suggest the gastric microbiome—a diverse community of stomach bacteria—may hold the key to combating this deadly disease.

A recent commentary published in the American Association for Cancer Research (AACR) journal Cancer Discovery highlights this potential paradigm shift underway in our understanding of gastric cancer.

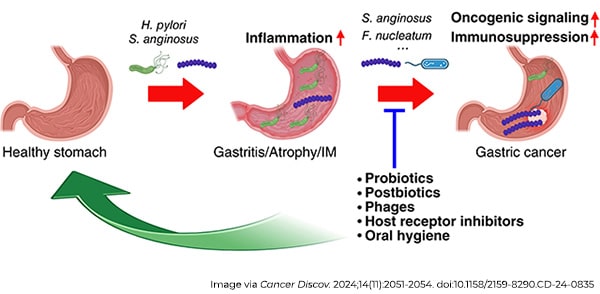

For decades, Heliobacter pylori (H. pylori) has been the primary suspect in gastric cancer research, and for good reason. It’s one of the few bacteria definitively linked to cancer, as it can trigger a cascade of changes in the stomach lining that can lead to tumor formation. However, recent data are changing our understanding of this complex disease and prompting researchers to reconsider H. pylori’s exclusive causal role. Such new insights could potentially open the door to better prevention, earlier detection, and more effective treatments.

H. pylori and a Delicate Ecosystem

H. pylori, which the World Health Organization has classified as a class 1 carcinogen since 1994, infects the stomach lining and can cause chronic inflammation, ulcers, and over time, cancer. In light of this knowledge, identifying and treating H. pylori infections has been a major focus of gastric cancer prevention.

But here’s the catch: most people with H. pylori don’t get cancer. This has puzzled researchers for years. What’s protecting some people while others go on to develop tumors?

Rather than being the result of a single “bad” species of bacteria, mounting evidence suggests that gastric cancer may arise from a microbial imbalance—a condition known as dysbiosis. Dysbiosis occurs when the natural balance of bacteria in the stomach is disrupted. Think of the gastric microbiome as a delicate ecosystem. When it’s in balance, the bacteria coexist harmoniously, maintaining stomach health. But when H. pylori or other harmful bacteria overgrow, they upset this balance, setting off a chain reaction of harmful changes.

A 2018 study revealed that as stomach tissue progresses toward cancer, its microbial community changes dramatically. Notably, bacteria like Streptococcus anginosus (S. anginosus), typically found in the mouth, became more prevalent—not particularly surprising given the physical connection between saliva and the stomach. Strikingly, these oral bacteria often persisted in the stomach even a year after treatment cleared H. pylori, and their persistence was linked to inflammation, tissue damage, and precancerous changes.

Even stronger evidence has emerged over the past couple years with direct demonstrations of the gastric cancer-promoting roles of S. anginosus as well as Fusobacterium nucleatum and Prevotella melaninogenica. Furthermore, S. anginosus appeared to synergize with H. pylori, the two seemingly working together to amplify inflammation and accelerate tumor growth.

This points to the broader and more complex polymicrobial reality of gastric cancer, and it’s likely that networks of microbes work in tandem to flip the switches necessary to drive each step of stomach tumor development.

New Approaches for Prevention and Early Detection

These findings open the door to new diagnostic tools. Current screening methods focus primarily on H. pylori, but this approach has limited predictive value since most H. pylori-positive individuals do not develop gastric cancer.

The discovery of other cancer-promoting bacteria offers a promising alternative. Identifying other microbes, particularly those more abundant in advanced stages of gastric precancerous progression, could offer a more reliable way to diagnose developing gastric cancer. This approach could leverage microbial biomarkers to identify high-risk individuals earlier and more accurately.

Already, one study hinted at the potential value of analyzing the bacteria in the saliva of patients: Changes in specific bacterial species were linked to different stages of progression, and in the future could provide important biomarkers for early detection in the clinic. Beyond saliva, gastric fluids and fecal samples may also hold promise. Collectively, these efforts could pave the way for population-wide screening programs, helping to identify high-risk individuals for follow-up endoscopy, especially in regions where gastric cancer rates are high, and access to health care is limited.

If we know certain bacteria are linked to cancer, could we stop the disease by targeting those microbes? It’s a promising idea. Current prevention strategies often rely on antibiotics to eliminate H. pylori. But what if we could go further by using probiotics or prebiotics to restore a healthy microbial balance in the stomach?

Efforts in the realm of personalized medicine—aimed at tailoring treatments and prevention strategies based on an individual’s unique microbiome—could also make a difference.

A Global Perspective: Why It Matters Now

Gastric cancer is the fifth most common cancer worldwide, but its burden isn’t evenly distributed, as East Asia accounts for nearly half of all cases. In China alone, there are an estimated 300,000 new cases of gastric cancer annually, a stark contrast with the estimated 27,000 new cases that will occur in the United States in 2024. Interestingly, more than 500 million people in China—over one-third of the population—carry H. pylori. Yet, only a small percentage of them will go on to develop gastric cancer.

Expanding screening programs to include microbial biomarkers could revolutionize how we identify and manage gastric cancer risk. By incorporating a wider spectrum of gastric microbiome biomarkers—that reflect additional bacteria linked to tumor progression or dysbiosis patterns—we could more accurately pinpoint individuals at high risk. This would enable earlier interventions, potentially preventing cancer from developing or catching it at a more treatable stage, ultimately saving lives.

The post Gastric Cancer: Looking Beyond H. pylori appeared first on American Association for Cancer Research (AACR).