For two years, Oya Gilbert visited a series of doctors as he continued to experience progressively worse episodes of shortness of breath, fatigue, and tremendous pain. Eventually, his doctors labeled him a hypochondriac and started “feeding” him anxiety pills that only made him feel more exhausted. After he got into a minor car accident, he felt like the lack of answers meant his death was likely not far off.

He decided to increase his life insurance to put his children in a better financial position. After years of wondering, hoping, and searching for an answer, he would finally get one. The insurance company’s doctors discovered the protein markers in his blood and urine that led to his diagnosis of multiple myeloma. He was stunned by the diagnosis, the lack of a cure, and the fact that Black people had double or higher risk of dying from myeloma.

“I live in a rural area—predominantly White,” Gilbert said. “It’s difficult for doctors to know anything about African Americans if you rarely see them, or maybe have some prejudgments about them. This region is known for prescription addiction. So, they were thinking that’s what I wanted. They just didn’t listen. If they’d listened, I think we could have gotten past a lot of those issues leading up to my diagnosis that just got brushed off.”

To raise awareness of disparities like these and bring attention to the importance of cancer disparities research in reducing health inequities, the American Association for Cancer Research (AACR) launched its Cancer Disparities Progress Report in 2020. Published every two years, the third edition—which was released May 15, 2024—shares nine patient stories like this one from Gilbert while also diving into the latest statistics to highlight how factors such as race, ethnicity, age, sexual orientation, gender identity, socioeconomic status, and geographic location can factor into the development of cancer and the care of patients.

Substantial Progress, But Not for Everyone

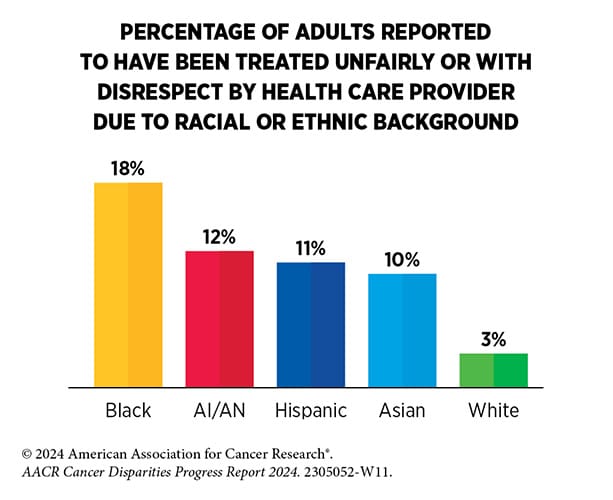

Substantial progress is being made in the fight against cancer. Overall, the death rate from cancer in the United State fell by 33% between 1991 and 2020 thanks to advances in prevention, screening, and treatment, but not everyone is benefitting from these equally, leading to disparities in cancer death rates between different populations. Black and Indigenous individuals have the highest overall cancer death rates in the United States, despite cancer incidence rates among these populations being lower compared to the white population.

As Gilbert discovered, that is especially true for certain cancer types such as multiple myeloma. It is also the case for prostate cancer, where Black men are twice as likely to die compared to white men, and breast cancer, where Black women are 40% more likely to die even though they have similar incidence rates compared to white women. American Indians or Alaska Natives are more than twice as likely to die from stomach cancer compared to white people.

These numbers can even be shocking for doctors who are intimately aware of a patient population. Phuong Ho, MD, an emergency room physician, had no idea about the rising incidence of lung cancer in Asian women who don’t smoke—four times higher compared to white women according to one study cited in the report—until she was diagnosed herself. Now she is an advocate for the Asian community and is participating in the Female Asian Never Smokers (FANS) study at the University of California San Francisco.

“I promote the study to the Asian communities through my friends and family, spreading the word to enroll because we need participation for this important research,” Ho said. “The Asian community, especially, might not have the awareness, health education, or access to medical care to have screening tests done, or even to seek out medical attention.”

The numbers can also be disheartening to racially and ethnically minoritized patients not only because of the inequalities they show, but also for the lack of detail within data sets that are insufficient in fully capturing the differential cancer burden within heterogeneous populations that have roots in different countries with social and cultural differences. For example, cancer statistics for Asians and Pacific Islanders are often aggregated together. As a native Hawaiian, Melissa Adams, a breast cancer patient, questions why these two groups are being lumped together.

“That does a disservice to everyone in that group,” Adams said. “To put that data all clumped together muddles the numbers.”

The report calls attention to the fact that collecting disaggregated data can offer a better understanding of the burden of cancer within racial and ethnic minority subpopulations.

Location, Location, Location

Adams also described the difficulty people in Hawai’i have in getting a second opinion or participating in clinical trials when the doctors they need to see or the trials they want to join are on the mainland.

“I had to buy plane tickets to go to the mainland,” Adams said when she was seeking another opinion on the next step in her treatment following her double mastectomy. “I still had drains in from my surgery and could not lift anything over my head. I needed help. My boyfriend had to take time off from work. That was a huge burden timewise, financially, and physically.”

But even smaller differences in location can make a big difference in care. Compared to those living in large metropolitan or urban areas, residents of nonmetropolitan or rural counties were 38% more likely to be diagnosed with and die from lung cancer. And the mortality rate for all cancers combined is 22% higher for residents in disadvantaged neighborhoods compared to advantaged neighborhoods.

That’s why Robert A. Winn, MD, FAACR, chair of the AACR Cancer Disparities Progress Report 2024 Steering Committee and director of the Virginia Commonwealth University Massey Comprehensive Cancer Center, says zip code matters. He coined the term “ZNA,” which refers to ZIP code and neighborhood of association, and he emphasizes the importance of considering an individual’s place of residence and other social drivers of health (SDOH) that could lead to inequities in care.

“The findings of this report offer a deeper dive into the ‘whole person’ as it relates to the areas outside of medicine that contribute to health inequities: ZNA, institutional and systemic racism, and situational and physical barriers to access, to name a few,” Winn said in a press release. “As we continue to look at cancer incidences and outcomes and cross-check them against these other factors, while having critical conversations that spur meaningful action within our affected communities, our path forward will become clearer. We have seen tremendous progress against cancer in the last few decades, but we must keep fighting to ensure equal access and improved health care delivery for all people.”

Closing Disparity Gaps

The report highlights many other disparities that need to be addressed—including a higher burden of cancer among sexual and gender minority individuals such as a 76% higher risk of being diagnosed with advanced-stage lung cancer for transgender individuals compared to cisgender individuals—but also identifies areas where progress is being made.

For example:

The overall cancer mortality gap between Black and white populations has decreased from 33% in 1990 to 11.3% in 2020.

Mortality from prostate cancer declined at a rate 5x higher in non-Hispanic American Indian or Alaska Native men compared to non-Hispanic white men between 2016 and 2020.

Stomach cancer incidence declined more than double the rate in non-Hispanic Asian and Pacific Islander populations compared to non-Hispanic white men between 2015 and 2019.

Mortality from liver cancer in non-Hispanic Black individuals declined more than 7x faster than in non-Hispanic white individuals from 2016 to 2020.

Hispanic women saw a decline in cervical cancer mortality that was 8x times faster compared to non-Hispanic white women from 2011 and 2020.

To build off this progress and to address all disparities still impacting cancer care, Todd Gates, a prostate cancer survivor, said three things are needed.

“The first one is funding,” Gates explained. “If you are going to get serious about it, provide the funding. The second one is funding … and the third one is funding.”

Where Further Action Is Needed

The report concludes with a call to action for policy makers, including some recommendations where additional funding might be the most impactful. For example, the report calls on Congress to appropriate at least $51.3 billion for the National Institutes of Health and at least $7.9 billion for the National Cancer Institute (NCI) in fiscal year 2025. Further, to help better control cancer, investments should be made in screening for early detection and prevention, such as by appropriating $472.4 million for the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s Division of Cancer Prevention and Control.

Two other barriers to health equity have been the lack of diversity in biospecimens used to study cancer etiology—which to this point have mostly been based on individuals of European ancestry—and the lack of sociodemographic diversity in cancer clinical trials.

While several efforts are underway to collect more diverse data sets, including the AACR Project Genomics Evidence Neoplasia Information Exchange® (AACR Project GENIE®), African Cancer Genome Registry, Avanzando Caminos (Leading Pathways) Study, Black Women’s Health Study, Multiethnic Cohort Study, Southern Community Cohort Study, and Women’s Circle of Health Study, the report calls for more initiatives in this area.

Additionally, even though programs such as the AACR and Bristol Myers Squibb Foundation’s partnership on the Robert A. Winn Diversity in Clinical Trials program and workshop are working to increase access and participation in clinical trials, further efforts are required to continue to close gaps and ensure more representation in trials.

“Not all the drugs act the same way on everybody,” Winn explained. “Not just because of your race, but the place and space that you also live. We need to do better, and probably will have to come up with new ways of figuring out how to make our trials much more accessible to all people who are suffering with cancers.”

Greater diversity will also be needed in the cancer research and care workforce, which is something the NCI is striving to increase through its Center to Reduce Cancer Health Disparities, and several other organizations are working to improve by increasing the availability of Science, Technology, Engineering, Mathematics, and Medicine (STEMM) educational and career pathways.

Finally, the report suggests two other actions: implementing policies to ensure equitable patient care and enacting legislation to eliminate health inequities.

“In this era of extraordinary scientific progress against cancer, it is crucial that we ensure that no populations or communities are left behind,” Margaret Foti, PhD, MD (hc), chief executive officer of the AACR, said in a press release. “Health equity is a fundamental human right and must be a national priority. We hope that the information and recommendations in this report will inspire collaboration among stakeholders and the necessary support from Congress to tackle these complex issues and eliminate cancer disparities once and for all.”

The post Cancer Disparities: The Gaps and Encouraging Progress appeared first on American Association for Cancer Research (AACR).